**Cover image for this article was generated using DALL-E-V3, provided by Microsoft Co-Pilot using text from this episode.

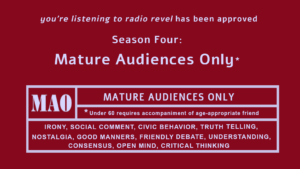

In celebration of Father’s Day, we’ve got together for a Break/Fix Podcast Crossover episode with a guest who has a dynamic relationship not only with cars, but the world around him. Growing up in the Midwest, maturing in New York City and finally setting down roots in Europe, podcaster Revel Arroway shares his life’s journey each week on You’re listening to radio revel.

Instead of our usual interview, we just handed the mic over to Revel to let him tell his own story in which cars have always played an important part, as did his stepfather Mike (above).

Spotlight

Revel Arroway - Hosts for You're Listening to Radio Revel

I retired from active ESL teaching in 2014. Before that retirement, I had spent 32 years in the profession. My last work was in a small, private academy in the North of Spain, working with a maths teacher, a French teacher and an elementary teacher. My work was a combination of helping kids with their school learning and teaching English as a Second Language.

Contact: Revel Arroway at Visit Online!![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] BreakFix podcast is all about capturing the living history of people from all over the autosphere, from wrench turners and racers to artists, authors, designers, and everything in between. Our goal is to inspire a new generation of petrolheads that wonder, how did they get that job? Or become that person.

The road to success is paved by all of us. Because everyone has a story.

Crew Chief Eric: Tonight, we’ve got a special guest with a dynamic relationship, not only with cars, but the world around him. Growing up in the Midwest, Maturing in New York City and finally settling down roots in Europe. Podcaster Revel Airway shares his life’s journey.

Each week on your listening to Radio Revel, instead of our usual interview, we’re just going to hand over the mic to Revel and let him tell his own story in which cars have always played an important part. So with that, revel, welcome to Break Fix. Well, thank

Revel Arroway: you, Eric for inviting me to do my thing on your [00:01:00] podcast.

Let’s go for it.

My stepfather, Mike, was diametrically opposed to who I was when he entered my life. I was a sensitive 12-year-old who’d lost his dad only two years earlier and had gained a certain level of independence through my mom’s prolonged mourning at the loss of her young husband. Mike was this Bulgar small town redneck, only 10 or 12 years older than me.

He drank beer instead of water. He sucked on skull chewing tobacco and spit in a tin can scattered about the house. He was missing all of his upper teeth, was balding, and had very severe psoriasis all over his face and neck and upper arm. He also smelled bad.

While I liked to listen to show tunes and classical music, Mike liked listening [00:02:00] to classic country western. His 8 track collection of Dolly Parton, Conway Twitty, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, etc. was impressive and always blasting as he drove. While I read Dickens and Tolstoy, Mike would read Nothing or an occasional Zane Grain novel.

Mike ate a raw onion with each meal. He ate Vick’s vapor rub, spread on toast when he had a cold. He was depressive, sometimes abusive, and almost always drunk. How had my mom picked him as her new husband, as the father figure for her three kids? And how were he and I ever going to bond? We had at least six years ahead of us living under the same roof.

Something would have to be done. I could say I’ve been driving now for 50 years, but why not? And grind eyes that by saying half a century during that half a century, I’ve driven over 30 different [00:03:00] cars, at least 20 of those with my name on the registration papers that kind of makes me a car guy, right? I got my learner’s permit back in 1976 and had the best driving teacher anyone could want, my mom.

Always patient, always clear in her instructions and explanations. She helped me learn how to take a curve, how to pull up to a stop sign. How to treat other drivers like other fish in the pond rather than like obstacles in my way. Problem was she wasn’t very good at parallel parking, that one I had to learn on my own.

While the written test was pretty simple, what action do you take at a red light, I failed the first behind the wheel exam despite the three months driving everywhere with my mom. The day before my exam, riding the school bus in the morning, and probably dreaming about how cool it would be to drive to school instead, a schoolmate, who had probably just gotten his license himself, decided to pass our bus on a country [00:04:00] road.

He didn’t see that directly ahead of the school bus was a fuel truck, braking to make a left turn into a farm lane. That boy broadsided his shiny new Ford pickup into the tank of the truck, knocking over onto its side, squishing his pickup like an empty beer can. Whatever flammable liquid that had been in that fuel truck was quickly extending into a wet, dark stain across the highway.

Now our driver managed to stop the school bus before we became an integral part of the crash site. She nervously shouted at the kids to stay in their seats as she tried to radio in the accident. Someone had to tell her she was talking into the backside of the mic. We had to wait for the police to arrive and tow trucks to clear the highway of the wreckage, the fire brigade, to pry that teen driver from the cab of the Ford.

Surprising to see him walk away from that accident on his own legs. All this meant that we had a good, long, rubber necking experience there, taking in and almost [00:05:00] memorizing the nasty scene ahead of us. That incident was still fresh on my mind as I took my own driving exam the next afternoon. I was scared, nervous, skittery, jumping at every car driving up from a side street, finally stopping at a red light, right in the middle of a busy intersection, in the middle of the exam.

This was small town America, and the tester knew about the accident, so he ticked a box on the form on his clipboard. Told me not to worry, come back in a week or so and try again. I’d probably be calmer once some time had gone by. And that turned out to be true, and I did pass the driving exam the next week.

I was pretty active in after school activities, and had always struggled with getting a ride into town or back home from theater rehearsals or student senate meetings or club meetings. And my folks were not at all willing to taxi me around. More than once I’d had to walk [00:06:00] four miles to catch a ride with my stepfather when he got off his shift at the sugar beet processing plant.

Once I had my license in hand though, Mike immediately gave me his car to use to drive to school. And bought himself another car to fix and drive.

That first car I dubbed my auto. In a pretentious effort to stand out from my classmates that all called their cars my car. As they walked around from class to class in the school hallways, casually jingling their car keys as a kind of status symbol that said, I have a car. No one kept their car keys in their pockets.

Anyway, I thought I was being more cultural, though I wouldn’t ever give my car a name. I would always call it my auto.

And I was the only student at my high school who drove a car like mine. A 1957 Buick Century four door [00:07:00] Riviera. Blue door panels, white on the top, wide bench seats in the front and back. I could pack in all seven of my best friends. I can’t remember. But I don’t think there were seatbelts for everyone. I don’t think there was even a seatbelt for me.

You didn’t need a key to start it up. Just switch that switch on the dashboard to the right and press softly down on the accelerator. High beams activated pressing the foot button on the floorboard just to the left of the parking brake pedal. A gas guzzler to be sure, 10 gallons per mile, uh, no, 10 miles per gallon.

But this was just before gas prices soared from 57 to 62 cents a gallon, so little damage to my pocketbook. I got an after school job at Kmart to pay for the gas. Mike was a semi professional automobile mechanic, which meant he knew a lot about cars. And wasn’t afraid to break them down and put them back together.

Something he did to each and every car he ever owned. Even the [00:08:00] Datsun pickup he bought brand new. Mike believed firmly that in order to drive a car, you had to know everything about how a car worked. Had to get your hands dirty. Crawl under the thing and struggle with that oil filter. Check the oil regularly.

Watch the tire pressure, know how to fix something, preferably before it broke.

Even before I got my license and started driving, my mom would send me out to the garage to help Mike as he took cars apart. My folks probably considered it that bonding exercise we sorely needed. I was the effete stepson who grudgingly learned what a piston ring or a torque wrench was and why it was.

I was the stepson who froze his skinny ass off waiting for Mike to shout out, Hand me a wrench or go get me another beer! Over Dolly Parton berating some woman named Jolene on the 8 track. And though I really didn’t like the getting your hands dirty part of the experience, The taking apart and [00:09:00] putting back together did fit right into my character.

You see, before Mike came into my life, I was a figure out how it works kid. I took apart everything I could get my hands on. I was probably only nine or ten when I got in trouble for disassembling an old pocket watch that was probably meant to be handed down to me at a certain age. I got my hands on it, got it opened, and managed to not take out an eye as the mainspring shot out at my face.

Despite the chewing out I got, my folks decided the best consequence was to make sure I always had something to take apart and put back together. So they were always giving me stuff to work on. An ancient royal typewriter, a singer pedal sewing machine, Any old appliance that would fit on a work table. I was always taking something apart and putting it back together.

So, working on cars was a practical application of what might have otherwise been seen as destructive [00:10:00] behavior. Over the first years trying to bond with Mike, I learned to handle a lot of mechanical work myself. When I heard that squealing sound from the right front wheel, I knew that I needed to have a look at the wheel bearings.

Mike would go for a ride with me, confirm the diagnosis, we’d head over to Western Auto, pick up a spare part and spend the afternoon taking out the old, replacing it with the new. Mike never complained about having to help figure out or fix a car for anyone. I’m in the parking lot at Kmart. Just got off work.

It’s 9. 30 at night and kind of cold. I sit in the driver’s seat of that 57 Buick Century and beat on the steering wheel and curse. I can’t get the thing to start. It just doesn’t make a noise, not even the groaning, death click sound of a dead battery. I finally give in and go to a phone booth outside the store and call home, asking [00:11:00] Mike if he could drive out and help me get the thing started.

He paused, sighed, but of course said he would. While I was waiting the 20 minutes Mike could take to drive into town, I began fooling around with starting the car again. That’s when I figured out what was wrong. The indicator in that little window over the steering shaft wasn’t set to P or N, it was pointing to D.

Of course the thing wouldn’t start. I shifted the gear, pushed down on the gas pedal, and the car started. I drove home, and Mike must have seen me as we crossed on the highway. The car was recognizable even at night. He pulled into our driveway just after me, even before I’d made it to the front door. I made up a story about a loose battery cable, which he would approve of me fixing more than the stupid, it was in drive, truth.

His only comment was that I could have waited for him to arrive before driving [00:12:00] off.

There were times there wasn’t much I could do. A few years later on a road JCs, some kind of small convention a couple of hours from home, I was having trouble keeping my 1972 Chevy Monte Carlo on the right. It wanted to veer to the right as I took each curve on the highway. There was a bit of resistance, a clunk here or there, but I made it to the convention.

Later, though, as I was pulling out of the parking spot at the end of the day, there was that bolt breaking crack, and the steering wheel no longer obeyed my commands, just flopped from side to side like a chicken head on a rung neck. Had to leave the car there at the local garage and come back a week later to pick it up.

Mike told me that had this happened at home, he’d have fixed it in a day. Mike didn’t like leaving our cars in the hands of other mechanics.[00:13:00]

Crew Chief Eric: Sorry to break into the story here, Rebel, but I’m curious, whatever happened to that 57 Buick Century? That’s kind of a classic car. Well, as Bette Midler would

Revel Arroway: say, a classic, eh? Well, that would almost make me a classic. That car was only two years older than me and was only 18 years old when it came into my hands.

Well, there was kind of a bittersweet ending with my auto. Mike wasn’t the kind of guy who could hold a job for very long. I kind of remember him having had a work accident and being on workers compensation for a while. But he finally packed up the family, everyone except me, and moved them all from Colorado to Illinois in the middle of my senior year in high school.

I talk about that teenage trauma in Season 3 of my podcast. It’s Episode 12, [00:14:00] called Get a Job. Anyway, while I was finishing up my last months of high school in Colorado, I stayed with an aunt of Mike’s, Josephine. But everyone called her Tood. She lived in a trailer park about six miles from town. The first couple of months living with her were fine.

I had my car, I had my activities, but I didn’t have any money. I wasn’t working and my folks only saw fit to send me 50 bucks a month, which didn’t even pay for gas money. I ran out of gas one afternoon, coasted the tank into a parking space, almost hit the building in front of the space because the power brakes didn’t work if the engine wasn’t running.

I walked home and drove me into town the next morning, lent me 20 bucks to buy gas to drive the car home.

Not long after that I had to pass the state vehicle inspection, which I did not. The brakes were pretty worn out. That could be heard every time I drove the thing. [00:15:00] I didn’t have the money to change the brake shoes or pay the inspection, so the car ended up parked alongside Tood’s trailer. Now, the car still ran just fine.

I just couldn’t use it. Tood dropped me off in town for school on her way to work. After school, I’d catch a ride back home with her. Sometimes my friends would give me a ride. And sometimes when I just needed some privacy, I would sit in the sentry after school, listen to the radio, try to think about my future.

It wasn’t particularly rosy. I was frustrated by not having any way to get around. I felt trapped. But the Sentry was kind of a safe space for me, and I was comfortable in it. One afternoon, as Tud and I made it home, I noticed that the Sentry wasn’t parked beside the trailer. For a very short moment, I had the fleeting hope that a guardian angel had taken the thing to get the brakes replaced, the inspection done, but that lasted only long enough for Tud’s [00:16:00] son to inform me that he had managed to sell the car for 30.

He’d then given the money to Tud. Seems that my folks hadn’t given her any money for either my room or board. That was some pretty marginal parenting on their part, but, well, no, hard feelings. Not even at the time, just a teen getting a rude awakening. It probably didn’t be good. I did find out, though, that the guy who bought the car was a collector who later restored the 57 Buick Century four door Riviera 2.

to her glory. A couple years later, when I was in Colorado for Thanksgiving, I saw that century driving about town, restored to its original dignity. That car was, really, an auto.

The next few years between graduating from high school and starting university, I drove six or seven of those [00:17:00] cars. It was almost like driving take away. Mike would get his hands on a jalopy. We’d fix it up together enough for it to get me around. Then let me drive it until it needed fixing again. We’d junk that one and buy and fix another.

I can’t even remember what models or years. There were too many and were with me too little time. I finally bought myself a 1979 Mercury Zephyr the year before I entered the university. I was working, making pretty good money, and the guy who sold it to me, despite being a friend, talked me into taking out a GM loan.

Think. How not to establish a good credit record. That was okay at the time. Payments were more or less reasonable and I had a near new car for the first time in my life. Problem was, there was some kind of hidden issue in the turn signal control I couldn’t identify and the entire electrical system would shut down without [00:18:00] warning, usually when driving at night on a sinuous country road.

I should have suspected at the time that it had something to do with the headlights, but never did anything about it, and Mike kept his hands off the electrics in all cars. Then, when I began university, I couldn’t keep up with the payments, and Mike sold that Zephyr for me, paid off the loan, and for 50 bucks got me a 63 Chevy Impala.

It was kind of a demotion for me. From a bright, shiny, powder blue, nearly new Zephyr, to a rusted out, hand painted blue Zephyr. I was worried my status among my classmates would drop,

but not at all. While they had enjoyed me driving them all over town in the Zephyr, the Impala caught their imagination. It was just so ugly, it was kind of cute. They were amazed to see the road pass beneath my feet through the holes in the rusted floorboard, [00:19:00] which I, of course, fixed in the first week.

And when my classmates found out the price, more than one asked if Mike couldn’t find them a car like that.

So, one night, I pick up a friend at her house to go to a party, pull down on the stick on the shaft to put the transmission in reverse, and the stick breaks off in my hand. Turns out a poor weld on a previous break had given up. My car was stuck in reverse, and we weren’t going to make it to the party.

Except Mike insisted that all cars have a small, basic toolbox in the trunk. So I reached into my small, basic toolbox, and I pulled out a very large screwdriver, shoved it into the space the stick had been, and was able to lever the car into first gear. Then second, third being the highest gear. Then I drove slowly to the party all the [00:20:00] way in second, teasing the clutch so I wouldn’t have to downshift anywhere.

Mike took a look the next day and told me that I need to go to Kmart and pick up a do it yourself floor shift stick kit. I was kind of skeptical. Is that a thing? And who buys this kind of thing at Kmart? But he was right. There in the auto department, hanging on a shelf in that plastic package was all you needed to install a stick shift on the floor.

Hole cut through the rusting floorboard, levers bolted here and there in the clutch box, suddenly, Well, no, it took me an entire day and a half, but sure enough, I hit a sporty car with a three on the floor. Problem was, I’d switched two levers about, and reverse was first, and first was reverse, but I got used to it.

And the next owner of that car managed to make the fix I was too lazy to do. All those experiences with Mike [00:21:00] Breaking down engines, fixing transmissions, fixing floorboards, and changing bearings. Well, I’d say they gave me a pretty good background in cars, even if I wasn’t going to fix cars myself. That background helped me do an emergency bushing change in the start of my 72 Ford Galaxy in the parking lot of my university apartment in one afternoon.

It helped me earn brownie points from my boss here in Spain by correctly identifying three broken valves in the 79 Ford Fiesta he let me use to drive to corporate classes. It made me more confident in keeping up the maintenance on my 82 Seat 131 Super Mirafiori, the first car I bought for myself in Spain.

Yet, keeping your car up and driving it in Spain is very, very different from in the States. First of all, not everyone gets a driver’s license. It’s very complicated and very, very expensive. The written test involves almost memorizing a [00:22:00] long, complex set of rules of the road, which includes hundreds of picture graph road signs that usually make sense, but have complicated if then regulations attached to them that also must be learned.

The written test, 30 questions, of which you have to answer 27 correctly, Has at least five nasty trick questions. Well, after hours doing sample tests on the internet, I aced mine with only one silly error about where to stop at a stop sign. Forgot one of mom’s lessons, I guess.

The expensive part for novices is actually learning how to drive. There’s no such thing as a learner’s permit here. And you have to study with an official instructor from a private driving academy in a car with duplicate steering wheels and pedals. Naturally, these driving lessons are paid by the hour, and the cost can be high, especially if you fail the hands on the wheel exam.

Since you are required to do another [00:23:00] complete set of driving classes before you can do the exam again. I passed mine on the first try without the tester even paying attention. My instructor had told her that I was an experienced driver, 30 plus years back then, and I was told to simply drive around town for 15 minutes and end up back at the starting point while my instructor and the tester gossiped about other drivers who hadn’t passed the exam that day.

I didn’t even have to parallel park for her. Now, why did I have to go through all of that to get my Spanish driver’s license if I were an experienced driver? One big fat reason. The U. S. doesn’t use those international road signs. Everything is spelled out for Americans in plain English. European countries don’t accept American licenses, except during tourism, and even then it’s best to get that AAA international license, which is basically a translation of your license.

Yet between countries that do use those international road signs, there is [00:24:00] a license validation process that costs much less. In the end, since I only took three driving lessons so the instructor could tell me what the actual driving test would be like, I only paid, I don’t know, around 200 for my Spanish license.

Almost no one fixes their own car. It’s pretty much prohibited to do car work on the street. No one has driveways. Parking garages are communal. Everyone has to take their car to a mechanic for every kind of repair and maintenance. Now, there must be some do it yourselfers out there. The used parts market is not small, but I think most of those parts are sold to local mechanics with small shops.

There seems to be an auto shop every other block in most cities, cramped into a small commercial space on the ground floor of an apartment building. The car park in Spain has also changed dramatically since about the 1990s, where once there was a big used car market and [00:25:00] most vehicles seemed to be at least a decade old, or sometimes more.

Nowadays, it’s not all that common to see really old cars on the highway, though economic crisis and inflation is bringing the used car market back a bit. If you can, you try to buy a new car or at least a zero kilometer car. Repairs and maintenance are then handled by the dealer on our regular basis tied to the warranty, and that’s where I ended up about six years ago.

After an 87 Ford Fiesta diesel with monthly mechanic bills, followed by an 89 Citroen Saxo with bi monthly mechanics bills, I did the numbers, got some advice from a mechanic friend at work, and bought my first brand new car. A Romanian made Renault clone called the Dacia Sandero. Metallic gray. Air conditioning.

CD player. Bluetooth. Because

Crew Chief Eric: [00:26:00] everything is better with Bluetooth. 5.

Revel Arroway: 6 liters per 100 kilometers. Three year guarantee. Four years without regular vehicle inspection. In house maintenance and repair at reasonable prices. It’s at 189, 000 kilometers right now. I thought I traded in at 150, but it’s still getting me around.

It was cheap, around 7, 500, which I paid in cash. GM car loan lesson learned. Only one complaint, and this isn’t just with this Dacia. It’s with any car with one of those multiple function turn signal controls. Meaning all modern cars? That Zephyr I complained about earlier had combined the high low beam control with the turn signal stick and a little nub of plastic broke free inside the mechanism and I couldn’t signal my turns anymore.

I opened it up, saw the [00:27:00] problem, tried to glue it in place, but that never works. Ended up having to change that little plastic part. Cost me twenty dollars I didn’t have at the time. The brand new Dacia has done the same thing to me twice. Now there are the turn signals, the high low beam control, the fog lights.

And the horn, all on the same stick. That doesn’t matter. After this or that much use, some little bit of plastic breaks off inside there, and I can’t dim the lights, or they shut off entirely, or I can’t signal a turn. And I can’t fix it myself. These kinds of cars aren’t put together with normal screws. So, twice I’ve had to pay to get the entire thing replaced to get control

back.

Revel Arroway: You’d think the manufacturer would have been aware of how plastic reacts to prolonged high temperatures, especially when encased in a black plastic housing [00:28:00] and located directly under a big piece of curved glass that will likely focus direct sunlight onto that housing for several hours every day. Even Mike, with his limited understanding of things in general, would have realized that root cause of the problem.

Or maybe manufacturers knew programmed obsolescence? They made money off selling me two new control mechanisms. Which begs the question, does Tesla make money off of amputating people’s fingers with sheet metal car hoods?

So, that’s pretty much my take on cars. They are certainly a part of my life, not indispensable. I got away without a car for eight years in New York City. Subways and bikes, you know. I figure I’m not really a true car guy, but my stepfather, Mike, made sure I had the basics under my belt. Though he and I never truly [00:29:00] bonded, I did pick up Mike’s basic three rules of car repair.

Crew Chief Brad: RULE ONE

Revel Arroway: Sometimes you take something that isn’t working apart, you look at every piece, you can’t see anything wrong, you put it back together, not without having to partially take it apart again, and suddenly, like a magic trick, it works and you’ve really not done anything. That’s okay. Rule two. You will always have spare nuts and bolts after a repair.

Don’t stress out about them. Drop them in a tin can on that shelf over there. They’ll come in handy in a future repair. Rule three. A car repair isn’t a repair if you haven’t smashed or cut a finger in that blood. Let loose a fuck or a shit. Slap a bandaid on it and get that bolt tightened. You’ll heal.

Maybe there were four [00:30:00] rules. Okay,

Crew Chief Brad: rule

Revel Arroway: four. Always listen to country music when working on your car. That music just puts you in the right groove. Or are there five rules?

Crew Chief Brad: Rule five.

Revel Arroway: Dirty hands can be washed. Now those are lessons that can be applied to any of life’s adventures, don’t you think? A shout out to Mike, wherever you are.

Crew Chief Eric: I could go on, but maybe it’s back to you, Eric. Your show is actually three shows in one. Memoirs like this one, and then film fantasies where you talk about films you’ve seen, and then you have the Tall Tales series, which is your own fiction, mainly short stories. And in season four of your Listening to Radio Revel, you’ve got a story called Almost Brothers, in which a Seat 127 plays a kind of important part in the twist ending.

Was this story based on real events? Well, [00:31:00]

Revel Arroway: I wouldn’t be surprised. I mean, it’s a story about the kind of people that I met while I was living in the northeast of Spain, a town called Avila. Uh, you know, Spanish housewives who take care of the kids in the house. They never question their menfolk. The non inspired men who trudge to work, trudge back home, ignore their wives who are ignoring them.

They eat, they sleep, and start the whole cycle again the next morning. Even though I was thousands of miles away from any of my Midwestern homes, in which I lived in a lot while I was growing up, I recognize a lot of common denominators. So what inspired you to write that story? Well, I think it was me recognizing the kind of dedication, kind of a fervent dedication to cultural tradition here in Spain.

Now, I talked about Ávila in a particular episode, episode four of this current season. But living in Spain for the last 35 years, I kind of find that people define themselves by more ingrained traditions. They’re like these [00:32:00] scripts that everybody feels that they have to follow, uh, even younger generations.

Uh, you find a mate, you get married, you have kids, you spend every Christmas Eve at grandma’s house, you get a job, you buy a house, you buy a car, you drive to the beach in August for vacation.

Crew Chief Eric: But what about the Seat 127? That sounds like a real car. Well, that’s kind

Revel Arroway: of just another part of that script.

Almost another character. The Seat 127 was a pretty popular car in the 1970s. It was affordable. Uh, it was easy on gasoline. I think it had an 80 percent people space inside the car. A hatchback with seats that folded down if you were carrying around anything bigger than your brood. With modernizations in Spanish society after the end of the dictatorship, or better put, the death of Francisco Franco, well, the SEAT kind of represented a new kind of freedom for Spanish people.

I got a chance to drive a later model, [00:33:00] probably a 7980. It was a car that was lent by my boss to drive to corporate classes as an English teacher. It was an okay car, not a single luxury, and I think it had the worst headlights I’ve ever used when you’re driving on dark country roads with non reflective road paint.

That car, well, a workmate of mine was driving it, wasn’t paying attention to traffic, I think was a bit tipsy, and he ran it in the back end of a truck. I actually felt a little bit sad about that, when I heard about it. Kind of reminded me of the century, and That’s Chevy Impala.

Crew Chief Eric: Okay. One last question, revel.

You said you’ve driven a lot of cars, a lot of different models and years. Have you ever really been attached to any one of those cars? Listen, a car is a car

Revel Arroway: is a car I like to drive, but I don’t think I’ve ever been really attached to any vehicle. Certainly never felt any emotions. No, wait, that’s a lie.

Uh, when I sold my [00:34:00] Renault Espress, it’s like a small, closed pickup truck, uh, like a Datsun. Uh, that one, when they picked it up to take it to the junkyard,

mm,

Revel Arroway: I choked up a little bit. On the other hand, when I found out the guy who bought it actually fixed it, so he could drive it around, well Didn’t feel so bad.

I still see it on the road from time to time. Now that car is really a classic here in Spain.

Crew Chief Eric: Revel, as always, thank you for sharing your stories, your wisdom, and your time with us. But we’ve reached that part of the episode where I like to invite our guest to share any shoutouts, promotions, or anything else that we haven’t covered thus far.

Revel Arroway: Thanks so much, Eric, for letting me share this slice of my life with you and your listeners. It’s been a pleasure remembering those details from days gone by.

Crew Chief Eric: So folks, if you enjoyed this episode, and if you’re looking for something new and different to listen to when you’re behind the windshield, we recommend taking a step into Revel’s life.

His charming, candid, and [00:35:00] revealing memoir style podcasts You’re listening to radio rebel can be found everywhere you stream, download, or listen. Be sure to check out rebels website. You’re listening to radio rebel. wordpress. com for more information, and you can certainly look him up and chat more about his episodes or stories via Facebook and rebel.

I can’t thank you enough for coming on break fix and sharing your life and your stories with us. So keep up the good work and we’re looking forward to new and exciting episodes on your listening to radio rebel. Well, again, thanks so much, Eric. And until next time, merry motoring.[00:36:00]

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast, brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at gtmotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators Fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gummy bears, and monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be [00:37:00] possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Introduction to BreakFix Podcast

- 00:27 Meet Revel Airway

- 01:13 Revel’s Early Life and Stepdad Mike

- 02:48 Learning to Drive

- 06:06 First Car: The 1957 Buick Century

- 07:47 Mechanic Lessons with Mike

- 10:35 Challenges with Cars

- 21:44 Life in Spain and Driving Differences

- 28:38 Reflections on Car Ownership

- 34:27 Conclusion and Shoutouts

If you’re looking for something new and different to listen to when you’re behind the windshield, we recommend taking a step into Revel’s life.

His charming, candid, and revealing memoir style podcast “You’re listening to Radio Revel” can be found everywhere you stream, download or listen. Be sure check out Revel’s website yourelisteningtoradiorevel.wordpress.com for more information and you can certainly look him up and chat more about his episodes or stories via facebook.